Mid/Side Stereo Part 1: What it is, and how it works

By Rob Stewart - JustMastering.com - Last updated August 7, 2017

Mid/Side processors are very popular mixing and mastering tools. I will discuss Mid/Side processing in Part II of this series, but first, I will discuss how Mid/Side stereo works so that I can give you a better understanding of the benefits, risks and limitations of Mid/Side processing.

Stereo sound reproduction is made by taking two mono channels of audio (Left and Right) and playing them together with the loudspeakers placed at enough distance from each other that you can tell which sounds are playing through one speaker versus the other. Anything that makes the left channel distinct from the right channel (and vice versa) is what creates the illusion that sounds are coming from different places within the stereo sound field. If both channels were exactly the same, the only stereo effect you would hear would be based on where the loudspeakers are placed in the room, and how each speaker interacts with the environment.

"Mid/Side" offers another perspective on Stereo. The term "Mid/Side" comes from Mid/Side recordings (more on that later), and the term is the cause some misunderstanding. When thinking about the terms "mid" and "side", one might think that the mid channel is everything that is in the middle of the sound field, but that is not true. The mid channel is actually the sum of the left and right channels together (L+R). For example, assume you have stereo track of a flute playing in the left channel, and a bass guitar playing in the right channel. If you add them together to create the "mid" channel, you will end up with a mono file that contains both the flute and the bass guitar (i.e. the sum of the two), even though neither instrument played in the middle of the sound field.

The side channel is often thought of as everything that can be heard to one side or the other of a stereo recording, but that is also not true. The side channel is simply the difference between the left and right channels (L-R). Using our flute and bass example above, the side version of this will also be a mono file which contains the flute and the bass.

In this example, if both the mid and the side end up sounding very similar, why do we get “Stereo” when we play the Left and Right channels together? This is where things get interesting, and it has to do with something called “correlation”.

Let's pause to discuss some key terms

There are three key terms that we need to cover before we delve any deeper: polarity, phase, and correlation. You will often hear the terms "polarity" and "phase" used interchangeably in the audio field, but they are very different, and both play a role in stereo sound reproduction.

"Polarity" is the positive or negative orientation of a waveform, relative to another. If you have two identical waveforms and then invert the polarity of one of them, for the purposes of this article, we'll call your original waveform the "positive polarity" version, and we'll call the inverted version the "negative polarity" version. The negative polarity version is a mirror image of the positive version. The two waveforms will completely cancel each other out if you combine them together, leaving no audio.

"Phase" is about the position of a waveform in time, relative to another. For example if you apply a phase shift to a waveform, you will move (i.e. shift) it forward or backward in time. You will not hear any difference listening to the waveform on its own, but you will if you have a reference point such as another waveform. For example, if you apply a phase shift to one track in a mix, and leave everything else as is, you are then shifting that track forward or backward in time, relative to the rest of your mix which can be very noticeable in certain situations – for better or for worse. There is a lot more I could cover regarding phase, but the key point is that phase is about time orientation, which is very different from polarity.

"Correlation" is about polarity alignment between two channels. Let's go back to the polarity example, above. The negative polarity version is uncorrelated with the positive polarity version, because its polarity is completely opposite. When you sum these two uncorrelated waveforms together, you end up with nothing (no audio). If you flip the negative polarity version back to positive, you now have two identical, correlated waveforms. Sum them together and you end up with twice the amount of audio.

Side note: Ever wonder how to read a correlation meter? A positive value between 0 and 1 means that you have more correlated sounds than uncorrelated sounds (1 = completely mono). A negative value between 0 and -1 means that you have more uncorrelated sounds than correlated sounds (-1 = completely uncorrelated). A value of 0 means that you have a 50/50 mix of correlated and uncorrelated sounds in your mix, which will often create a wide, pleasing stereo sound field. Bearing this in mind, you want to aim for values between 0 and 1 when mixing to help ensure that your mix is mono compatible (an important feature for TV, film and radio broadcast).

The role that phase plays in Stereo and Mid/Side

Phase plays a role in correlation, because sound arrives at a given microphone at a point in time. If you set up two mics to record something in stereo, and your source is closer to the left microphone than the right microphone, the sound will arrive at the left microphone first. It may only be a few milliseconds, but that is enough of a time difference to create a phase difference between the left and right channels. That phase difference will de-correlate some of what was captured between the two microphones, resulting in a stereo capture of whatever you were recording.

If you mix the two recordings into a single (mono) channel, you may hear the effects of comb filtering (the uncorrelated portions of the spectrum getting cancelled out) depending upon how you positioned the microphones relative to the source and to each other, which is one of the reasons why microphone positioning is so important in recording. Comb filtering can make a stereo recording incompatible with monaural playback because the effect that it has can dramatically reduce tone quality.

Getting back to Mid/Side, imagine that you set up the two mics to eliminate the time difference with the direct sound. With only one source, and no difference in phase between one mic and another, would you end up with a monaural recording? No. In this case, the acoustics of the environment that you are recording in will also generate different time delays between the left and right microphones, and those tiny phase differences of the captured room reflections (blended with the direct sound) will create a stereo capture of the direct and reflected sound.

Boiling it down, phase plays a big role in stereo playback and mono compatibility, because it can impact the correlation between the left and right channels.

Here is another example:

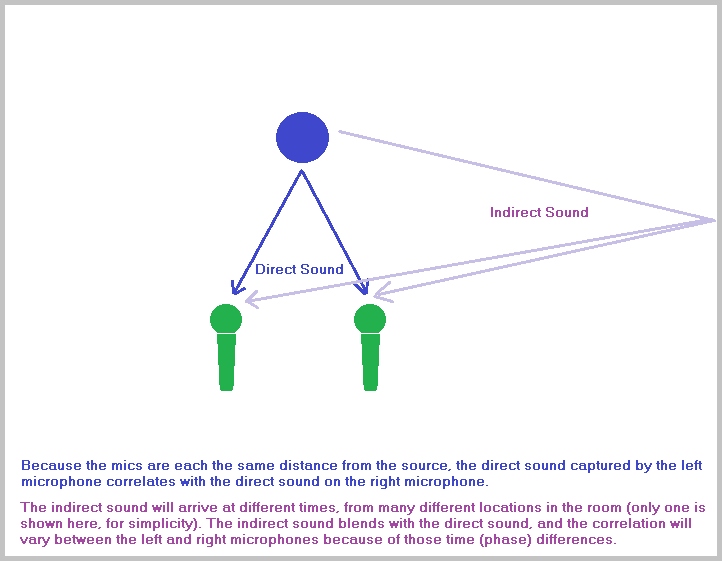

In this example, the direct sound captured by the left microphone will correlate with the direct sound captured on the right because it arriving at each microphone at the same time. If you only captured the direct sound in this example, you would have a mono recording, but the room acoustics are helping to create a stereo sound field.

The indirect sound coming from the room reflection has to travel a little further to get to the left microphone, meaning that it arrives a little later than on the right. This causes a slight phase difference between the left and right channels, causing portions of the indirect sound in the left channel to not correlate with portions of the sound in the right channel. Even though these microphones are perfectly aligned to capture the same amount of direct sound, the room acoustics play a role in what actually gets captured by each microphone. In other words, you are capturing a blend of correlated (direct) and uncorrelated (indirect) sounds, and that is what helps make stereo what it is.

Putting it all together

You need a mix of correlated and uncorrelated sounds for Mid/Side stereo to work (100% correlation results in 100% mono sound). Polarity allows you to encode stereo into Mid/Side or to decode Mid/Side back to Stereo, and the difference between the left and right channels determines what you hear in the mid (sum or L+R) and side (difference or L-R) channels.

Anything that creates equal or more audio when Left and Right are summed (i.e. correlates) will be heard in the mid channel, and anything that creates equal or more audio when the right is subtracted (i.e. does not correlate) from the left will be heard in the side channel. Because Mid and Side are really about the sum and difference of the left and right stereo channels, "Sum and Difference" is a more accurate term than “Mid/Side”.

Mid/Side recordings

Let's examine at how Mid/Side recordings are made. This is where the concept of "mid" and "side" came from, and why there can be some misunderstanding of what the "mid" and "side" components of stereo are.

You can make a Mid/Side recording by placing a figure-8 (i.e. bi-directional) microphone so that the null section is facing toward whatever you are recording, and then placing a unidirectional microphone just above it, facing what you are recording. The figure-8 mic is therefore set up to pick up sounds coming from the left and right, while the unidirectional microphone is intended to everything in the center. After you finish recording, you will have two mono tracks; one from the unidirectional microphone (i.e. the "mid" channel), and one from the bi-directional microphone (the "side" channel).

To reproduce stereo sound from these mid and side recordings, you first have to convert them into Left and Right stereo channels by Mid and Side together (Mid + Side) to create the left channel, and subtracting the Side from the Mid (Mid minus Side) to make the right channel.

Here’s how you do that in your DAW:

- Load the Mid and Side recordings into your DAW.

- Create a clone of the Side channel so that you have two Side channels (Side 1, and Side 2).

- Pan the Mid channel to the center.

- Pan the "Side 1" channel hard left.

- Pan the "Side 2" channel hard right.

- Invert the polarity of the "Side 2" track.

- Send all three channels to your master bus, and adjust the levels of the Mid relative to the two side channels until you get a realistic/pleasing Stereo spread (lower the side channels to narrow the spread, raise them to increase the spread).

To summarize, you create Stereo reproduction from Mid and Side microphone recordings by using polarity; the sum and difference between the middle microphone and two opposing polarity versions of the side microphone. Middle + Side = the left channel, and Middle - Side = the right channel. By blending Mid + Side and then Mid - Side in this fashion, you are using correlation (polarity) to recreate the differences between the left and right stereo channels, allowing you to reproduce the stereo sound field that you originally recorded with the microphones.

Where the misunderstanding about Mid/Side comes from

Relating this back to Mid/Side stereo, in a simple sense (i.e. not taking the microphone’s characteristics into account), the middle microphone is really picking up everything in front of it, not just the “middle” of the sound field, and that’s much the way you would want to look at Mid/Side stereo. “Mid” is really the sum of everything in the two Left and Right channels, not just the middle. “Side” is really the difference between the Left and Right channels, not just the “sides” of the sound field. This is why "Sum and Difference" is a more accurate term than Mid/Side.

In Part II, I’ll expand on this by discussing the benefits, risks and limitations of Mid/Side processing.

Happy mixing!